Galkayo and Somalia’s Dangerous Faultlines

By Zakaria Yusuf & Abdul Khalif

The silhouettes of armed men, some pirates and some homegrown security forces, appear on the horizon in the early morning in the semi-desertic plains near the central Somalia town of Galkayo on 18 August 2010. AFP/Roberto Schmidt

The silhouettes of armed men, some pirates and some homegrown security forces, appear on the horizon in the early morning in the semi-desertic plains near the central Somalia town of Galkayo on 18 August 2010. AFP/Roberto Schmidt

Clashes between clan militias in Somalia’s historically divided city of Galkayo that broke out on 22 November have killed at least 40 people, injured hundreds and displaced thousands. The fighting raises fears that the Galkayo dispute could escalate into a national conflict, and shows how fragile Somalia remains during its incomplete transition to a new constitutional order and peace.

The Galkayo clashes symbolise the folly of the Somali Federal Government (SFG) and its international backers – an extraordinarily wide range of actors including the UN, the African Union, the European Union, the U.S., UK, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Saudi Arabia – who are pushing for the top-down establishment of Interim Federal Administrations without parallel reconciliation processes between clans at a local and national level.

As long as these multiple administrations are not fully constituted and without their specific local political compacts in place, there will be fierce clan competition over their control and undecided borders. Galkayo is a clear example of what happens when peace is neglected over a desire to show progress. To complete Somalia’s transition, a greater focus on bottom-up peace processes rather than driving through top-down short-term political fixes is needed.

A History of Clan Conflict

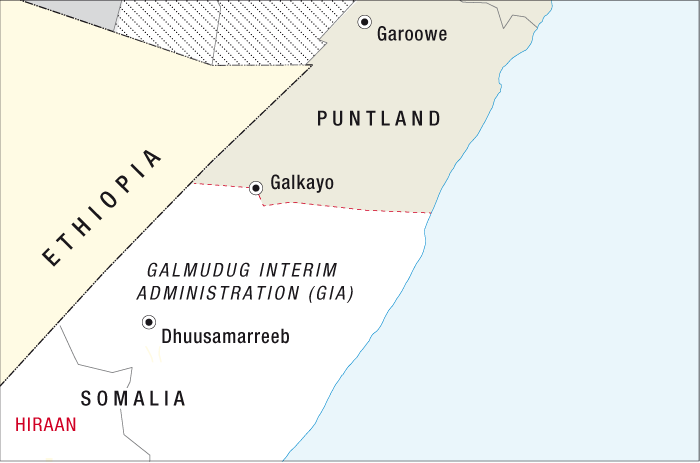

Galkayo (population 137,000) is divided between two federal states, the Galmudug Interim Administration (GIA), just established in 2015, and Puntland, formed in 1998. Its local divisions also mirror the larger divide between two dominant and historically rival clan families, the Darod and the Hawiye. The Darod (specifically Majerteen-Omar Mahmood sub-clan) dominate Galkayo’s Puntland-administered north, the Hawiye (specifically Habar Gidir-Sa’ad sub-clan) dominate the GIA-ruled south.

The divided city of Galkayo at the border between Puntland and the the Galmudug Interim Administration. CRISIS GROUP

The divided city of Galkayo at the border between Puntland and the the Galmudug Interim Administration. CRISIS GROUP

Italian colonial administrators divided Galkayo and its environs into clearly demarcated clan-based zones – via the “Tomaselli” line – as a solution to inter-clan conflict over land. Even the nationalist and declared enemy of clannism President Siad Barre could not overcome this divide during his 22 years in power. After Barre’s regime collapsed in 1991, Galkayo became a deadly flashpoint between mainly Darod and Hawiye militia. In 1993, clan warlords signed the Mudug Peace Agreement to divide the city and its key revenue sources – including the airport and main market – between the two main clans. This brought relative peace for the next two decades.

Now neighbouring Puntland feels that the new GIA threatens its authority over populations (especially clans) and the territory (the former Mudug region) it claims to control. It therefore rejected the formation of the GIA, claiming that it was unconstitutional, since it is based on just one-and-a-half states (Galgadud and the southern half of Mudug), while the Somalia Federal Government’s provisional constitution stipulates that two or more regions are needed to form a federal state. When Puntland declared itself a regional state in 1998 prior to any federal constitution it was based on two-and-a-half regions (Bari, Nugal and the northern half of Mudug). Both GIA and Puntland, however, are mostly an expression of the territorial claims of their respective dominant clans, the Hawiye-Habr Gedir and Darod-Majerteen.

Tensions between Puntland and GIA flared up again in September during consultative meetings on the 2016 national elections. Puntland’s President Abdiweli Gaas walked out in protest, claiming the GIA was not a legitimate federal entity. In October, arguments escalated over disputed landing rights when an aircraft landed in GIA-controlled south Galkayo instead of the north Galkayo airport under Puntland’s control – as per the Mudug agreement. But it was Puntland’s construction of a new road, which encroached upon the agreed lines of clan control between north and south Galkayo, that sparked the latest and most serious conflict.

Federal Intervention Generates a Truce – But Not Stability

A week after the clashes in November, SFG Prime Minister Omar Abdirashid Sharmake travelled to Galkayo with a delegation including traditional elders, representatives of the international community and presidents of other interim administrations – Ahmed Mohamed “Madobe” of the Juba Interim Administration and Sharif Hassan Adan of the Interim South West Administration.

By 2 December they had negotiated a fragile truce. The agreement stipulated an immediate ceasefire, withdrawal of militia from the front lines, return of displaced persons, and, optimistically, a solution to the “Galkayo question”. This first ceasefire collapsed after just one day amid heavy fighting.

Another truce agreed on 5 December is holding, but the situation remains tense. It has national ramifications. Puntland President Abdiweli Gaas accuses federal forces of providing military support to the GIA, whose president, Abdikarim Guled, was a former federal minister and remains close to the SFG president.

Galkayo and Somalia’s Future

In the short term, the SFG must continue to prioritise mediation in cooperation with their international and regional backers to ensure the parties respect the most recent ceasefire. Further violations could undercut its ability to mediate conflict in the future – a critically useful role fulfilled by the otherwise weak Mogadishu government.

In the long term, the SFG – with support from the international community – must work to clarify the status of Galkayo and the numerous other locations nationwide that are disputed between federal entities and their clan constituents. These are issues that the authors of the provisional federal constitution – including Puntland President Abdiweli Gaas, when he was still the federal prime minister – had left deliberately vague.

If the ceasefire is violated for a second time, this clan dispute could escalate into a wider national conflict between related Darod and Hawiye clans, especially because the two clan families remain political rivals on the national stage and are competitors for control of the presidency in 2016.

Even though the SFG’s mandate theoretically ends in August 2016, such targets time-tabled by national politicians and international diplomats are not worth the lives recently lost and potentially others elsewhere. The violence in Galkayo should serve as a reminder that any rush to finalise the federalisation process – without pause over particularly conflict-prone regions, or at the very least planning for deeper reconciliation processes where old disputes still fester – risks undermining the limited progress made in Somalia since 2012.